In the late 17th century, the church in the new territory of New France — what would come to be known as Quebec — waged a moral war against the government1 of said territory over its policy of allowing the sale of alcohol to the aboriginal population. Early governors ignored the implication and devastation that were caused in favor of easy profits and favor with commercial traders.

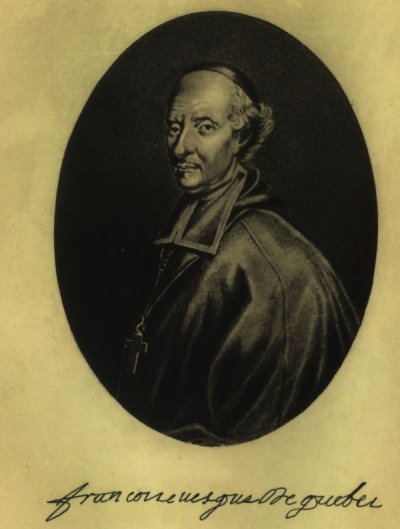

The first bishop of New France, Francoise de Laval, specifically went to King Louis XIV in order to circumvent what he referred to as “Statesmen who place the freedom of commerce above morality of action”.2 The Hurons, Algonquins, and Iroquois had no history of alcohol and it rampaged through their peoples much as the new viruses introduced from Europe.

“There is no species of madness, of crime or inhumanity to which they do not descend. The [Indian], for a glass of brandy, will give even his clothes, his cabin, his wife, his children; a squaw when made drunk—and this is often done purposely—will abandon herself to the first comer. They will tear each other to pieces. If one enters a cabin whose inmates have just drunk brandy, one will behold with astonishment and horror the father cutting the throat of his son, the son threatening his father; the husband and wife, the best of friends, inflicting murderous blows upon each other, biting each other, tearing out each other’s eyes, noses and ears; they are no longer recognizable, they are madmen; there is perhaps in the world no more vivid picture of hell.” 3

I resonate deeply with this. Regularly on our church grounds I have to confront those who have lost families, jobs, houses, and hope because of the drink. With nothing left, and nowhere to turn, they sleep in our corners and micturate on our holy grounds. Most recently I told a man he might stay and rest, if, and only if, he allowed me to throw out the full can he was holding. Sitting in his own urine, he chose to get up and push his walker somewhere else that he might continue in his spiral.

Dead men walking.

I wish and pray for hope and their salvation, but often there is little left to salvage beyond their souls. A moment, some food, and a quiet corner before being told to shuffle off somewhere else. That they ended up here, while their own choosing, is also the consequence of a market that prioritizes profit over conscience. The Christian gospel declares that human will and autonomy is a slave to sin.4 Ours, yes, but without God our choices are broken and lead to death and pain. The Christian conscience recognizes this, and mercy helps mitigate those consequences, until it’s too late, in which case charity must care for those poor lost folks.

In either the prevention, or ultimately and far more burdensome the care, they become our responsibility. As such, far costlier for all involved when we avoid our duties to our conscience and to our neighbor.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.